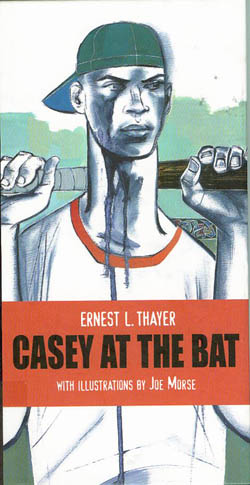

CASEY AT THE BAT, Earnest Thayer’s minor epic poem about baseball, gets a wholly fresh and nostalgia-free update by artist Joe Morse. Morse abandons the handlebar moustaches and turn-of-the-century trappings of previous editions. Instead, he brings the 1888 poem into the modern inner city.

To do that, the book’s design sets-up a slick transition from the Victorian Era to current time by placing over the first page a sheet of vellum watermarked with an old-timey logo for the Mudville Nine. The vellum overlays a heavily graffitied brick wall above which floats a word balloon filled with the poem’s title.

In it’s way, the vellum page is a visual cue identical to the first sepia-toned half hour of MGM’s THE WIZARD OF OZ. Dorothy steps out of her monochromatic front door into the Technicolored Munchkindland; the reader peels back the fogging page to reveal shapes and colors that have nothing to do with what we know of this poem.

In both instances, that simple transition signals that the story changed to a time and place different than the one we expected.

Morse then takes the first few pages to set the scene: a baseball field in an urban landscape, bleachers next to a highway overpass, serious looking inner city teens dressed in street clothes sizing up their uniformed (suburban?) opponents and the bus they rode in on.

A further piece of set-up takes place on a textless page where Morse employs comic book panels. Even before a single word of Thayer’s is read, we know from those eight panels — one for each brutal inning — that the Mudville Nine are about out of luck.

Having softly introduced readers to his use of comic book codes, Morse proceeds to place Thayer’s verses in a series of word and though balloons. There is no one person narrating the story. The words and thoughts belong to everyone in Mudville — an unseen announcer; people in the stands, on the street, or yelling from the balconies of nearby housing projects; some guy’s TV.

The array of people, places, and perspectives gives Thayer’s words more weight that they’ve ever had before, and maybe more than they deserve.

Thayer’s writing about the game of baseball. (Yes, I said it: GAME. The fate of nations is not decided upon it, nor is it a metaphor for life. It’s just a game; let it go.)

But Morse makes it clear something important is on the line here. It’s not as mere and shallow and pointless as team pride. The grim faces, muted pallet, and dripping accents manage to elevate the stakes — but what are they? Identity? Dignity, prestige, and self-image?

Hope?

Hope for whom, though? Casey? Themselves? Do they yearn to see a local boy make good so they can can vicariously live through his success?

It’s hard to say, exactly. Maybe it’s all that and more. Or not. Read the book and decide for yourself.

Morse’s choice of inner city setting combines with Thayer’s poem to create a great deal of new symbolism.*

Casey is no longer a defeated hero or an arrogant Gas-House Gorilla. Now, Casey is a young and undisciplined natural athlete who, thanks to his local celebrity status, pays for his overconfidence. And in the aftermath of Casey’s failure, Morse’s art beautifully illustrates the manic-depressive behavior and schizophrenic allegiance of modern sports fans.

One of the best and most surprising things about this book has nothing to do with the content. I found this not at a bookstore, but in the children’s section of my local public library. How great is that? You better believe some smart somebody in the ordering department is keeping a sharp eye out for books that use comics and sequential art techniques to tell more literary stories.

Rather than finding the library shelves filled with the latest attempt at reheating Classic Comics, young readers who normally absorb Manga and superhero books can also find CASEY AT THE BAT. Both will expand the literary palates of comic book readers, though CASEY is a more daring — and possibly a more satisfactory — choice for the library and the reader to make.

*In my opinion, there is also significant symbolism to be found in and around the fact that Casey is portrayed as a young black man. Being as how I’m an over-educated, middle class white guy from the ‘burbs, I don’t feel qualified to elucidate. However, I welcome any readers who care to give it a shot. Please contact me via comments or email with your analysis. If it’s coherent, I’ll consider posting it on the main site.

Casey At The Bat

Writer: Earnest L. Thayer

Illustrator: Joe Morse

Published in 2006 by KCP Poetry, a division of Kids Can Press www.kidscanpress.com

24 pages